HSUS Wants to be “BFF of the Court”

At the end of 2009, USA Today reported that the Humane Society of the United States employed "[a] staff of 30 attorneys—up from three when Wayne Pacelle took the helm five years ago." (And today the group placed a "help wanted" ad for yet another lawyer.)

Wouldn't it be nice to have a mid-sized law firm on your payroll, suing anyone you please and muzzling your critics with impressive-sounding threats?

Think about it: Thirty lawyers, even in the nonprofit sector, "bill" at least 60,000 hours of work annually. And it's fair to assume that the agenda-driven HSUS encourages its legal crusaders to work overtime to push animal rights; so that number is a floor, not a ceiling.

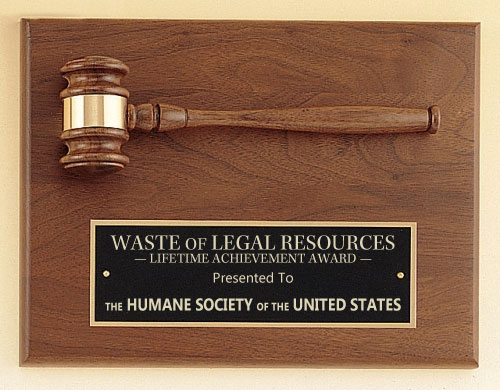

We were curious: Just what do these lawyers do all day? A big part of the answer is that they file amicus curiae (“friend of the court”) briefs with court clerks. Lots and lots of amicus briefs. (And frivolous lawsuits, too, but that’s a discussion for another time.)

HSUS has its own web page where it boasts about its various legal endeavors, but we decided to browse the courts themselves to see what else is going on. We discovered about three-dozen of these briefs, representing countless hundreds of hours of work. And all you well-meaning HSUS donors out there are paying for it—which would be fine if the court cases in question were about the cats, dogs, puppies, and kittens that turn ordinary people into HSUS members.

Are they? Not so much.

You might be surprised by the kinds of cases that draw the attention of HSUS’s legal guns. Here are just a few of our (not so) favorites:

- Monsanto et al. v. Geerston Seed Farms, Supreme Court of the United States, 2010 (HSUS supported the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals' nationwide injunction against planting genetically modified alfalfa, even though only a very remote possibility of reparable harm existed.)

- Del Gallo v. Parent, U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit, 2009 (Foreshadowing its own ballot-initiative tactics, HSUS weighed in on a case about whether political candidates can collect petition signatures outside post offices.)

- Winter v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Supreme Court of the United States, 2008 (HSUS argued that the U.S. Navy should have to commission a lengthy Environmental Impact Statement before conducting ocean sonar exercises—despite having already completed its own environmental assessment.)

- Natsios v. National Foreign Trade Council, Supreme Court of the United States, 1999 (HSUS defended Massachusetts for not conducting commerce with companies that did any business with Burma.)

- Metcalf v. Daley, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, 1999 (HSUS opposed an Indian tribe’s right to hunt whales for subsistence.)

Some of the briefs we found did have a direct relationship with animal welfare issues (like supporting a locality’s right to ban cockfighting). But then there are some serious head-scratchers that appear to rely on a two-degrees-of-separation model. For instance, HSUS justifies weighing in on genetically modified food because livestock eat alfalfa.

By this kind of logic, HSUS could start filing briefs in just about any federal court case. (“Well, your Honor, a lady spilling hot coffee on herself while driving might cause her to swerve and hit a squirrel, so we feel compelled to intervene.”)

The billable hours required to prepare just one of these briefs would cost about $20,000 at a white-shoe DC law firm. Multiply that by HSUS's case load, and … well, that's a lot of money that's not going toward the homeless pets in HSUS’s commercials. (Or by another measure, an in-house lawyer's salary to write and research this stuff represents money that could fund your local pet shelter instead.)

You don’t see too many briefcase-toting members of the lawyer class in HSUS’s ads, asking for "$19 per month." That's probably because homeless kittens can open more checkbooks than legal sharks.