HSUS: Animal ‘Rights’ Means Letting Animals Sue You

We’ve walked you through the essential differences between animal welfare and animal rights on a few occasions, arguing that HSUS is an animal rights group and has been for a long time. But for those of you who slept through the last class, here’s the essential difference again.

We’ve walked you through the essential differences between animal welfare and animal rights on a few occasions, arguing that HSUS is an animal rights group and has been for a long time. But for those of you who slept through the last class, here’s the essential difference again.

The animal welfare philosophy says that we should treat a cow with kindness before we turn it into hamburger. This is what about 99 percent of Americans believe.

The animal rights position, however, holds that we should never, under any circumstances, turn a cow into hamburger.

You can easily extrapolate this logic to hunting, fishing, fashion, circuses, medical research, and a host of other human activities. But the bottom line is that animal “rights” is an abolitionist, absolute philosophy with absolutely no wiggle-room for human nature. It’s also the philosophy that some of the Humane Society of the United States's leaders (including its current President) have shared.

The latest evidence for this comes from the Harold D. Guither Collection in the University of Illinois Archives. After we reviewed one of Guither’s books a few weeks ago, we went digging. And we found in Guither's papers the clearest example yet of HSUS’s leaders plainly describing an “animal rights” vision to their own members.

Alert HumaneWatchers will remember that last April we unearthed a fascinating document in the Google Books archive: an essay published by Vegetarian Times in 1982, which laid out HSUS’s earliest known support for animal rights.

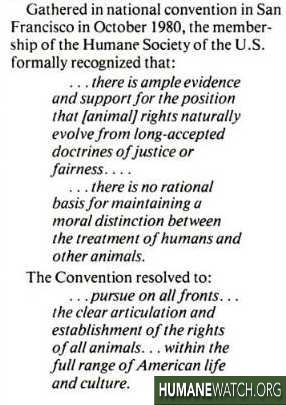

That essay told the story of HSUS’s 1980 convention, at which the organization resolved to “pursue on all fronts … the clear articulation and establishment of the rights of all animals … within the full range of American life and culture.” (Ellipses in the original.)

Thanks to the Guither archive, we now have an example from ten years later of HSUS developing this fringe philosophy.

In 1990, HSUS distributed a fundraising leaflet through the mail titled “A Discussion … Rights For Animals.” The long-winded tract read more like the musings of a PETA lawyer than today’s touchy-feely Wayne Pacelle fundraising mailers. But from its first sentence, it firmly established HSUS as one of PETA’s fellow travelers:

In 1990, HSUS distributed a fundraising leaflet through the mail titled “A Discussion … Rights For Animals.” The long-winded tract read more like the musings of a PETA lawyer than today’s touchy-feely Wayne Pacelle fundraising mailers. But from its first sentence, it firmly established HSUS as one of PETA’s fellow travelers:

The Humane Society of the United States has long been in the forefront of advocating the recognition of rights of and for animals.

Lest you think HSUS means something entirely different by “animal rights,” the authors go into significant detail.

You may recall that in the first weeks of the Obama Administration, there was considerable concern in Washington about the President’s choice to lead the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. The writings of Harvard law professor Cass Sunstein, who would ultimately win Senate approval for the “regulatory czar” job, raised the hackles of many lawmakers. This was because Sunstein believed animals deserved the right to sue people in court.

That near-stalemate in early 2009 was only resolved when a contrite Sunstein promised three different U.S. Senators that he would not use his bureaucratic power to create new legal rights for animals.

At the time, many observers thought Sunstein was a social-policy radical who worshiped at the feet of Peter Singer. It now looks like he wasn’t the only one. Singer’s Animal Liberation was published in 1975. By 1980, HSUS was pledging itself to the cause of securing “the rights of all animals.”

And by 1990, HSUS was spelling out the same fringe courtroom philosophy that would nearly make Cass Sunstein a punchline 19 years later.:

[Animals] are viewed as having no inherent capacity to invoke the protection of the state, and their entire legal status is underpinned by constitutional doctrines that deny them recognition as "persons."

Access to the courts is such a powerful right and would pose so revolutionary a threat to the established order that it will probably be among the last of animal rights to be recognized, requiring statutory, even constitutional, changes.

You read that right. Less than two decades ago, it was the Humane Society of the United States’s stated position that (1) all animals should have legal “rights”; and (2) achieving those rights for animals might require the U.S. Constitution to make room for lab rats. (We’re not sure how James Madison would feel about this.)

HSUS writes that animals should enjoy the legal right of having "third parties" sue on their behalf. "The critical goal," HSUS explains, is "getting litigation into a format where someone with ready access to the judicial system is representing the animal and its interests and only the animal and its interests."

This is a clear precursor to what Cass Sunstein would later write, in 2004:

[A]nimals should be permitted to bring suit, with human beings as their representatives, to prevent violations of current law … Any animals that are entitled to bring suit would be represented by (human) counsel, who would owe guardian like obligations and make decisions, subject to those obligations, on their clients’ behalf.

Of course, the question of just who will “represent” the animals in court is an open one. But HSUS has more than 30 attorneys on staff.

Here’s how HSUS summed up its blueprint for animal rights in that 1990 fundraising mailer (emphasis added):

[I]n all available forums, animal advocates must continually assert the notion that animals’ fundamental interests deserve to be weighed against competing human interests before use or exploitation of animals is permitted or continued.

Recognition of legal rights will follow.

When Wayne Pacelle took over HSUS in 2004, he moved the organization (largely) away from philosophical discussions like this, probably because he understood that cute pictures and creatively spliced videos do a better job of raising money than dry academic treatises. But that doesn’t mean Pacelle ever abandoned the endgame envisioned by his predecessors.

When Wayne Pacelle took over HSUS in 2004, he moved the organization (largely) away from philosophical discussions like this, probably because he understood that cute pictures and creatively spliced videos do a better job of raising money than dry academic treatises. But that doesn’t mean Pacelle ever abandoned the endgame envisioned by his predecessors.

And if the “Rights For Animals” philosophy sounds like something the more infamous PETA might argue for, you get a gold star. The primary difference between HSUS’s Wayne Pacelle and PETA’s Ingrid Newkirk is that Newkirk is almost pathologically honest about how radically she wants society to change.

Pacelle is far better at hiding the ball. But every so often, a glimpse at HSUS’s history gives us a reality-check.