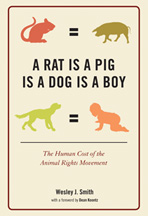

Rats, Pigs, and Dogs: Oh Boy!

When Wesley J. Smith first told us he was thinking of writing a book about the animal rights movement, our initial reaction was one of very cautious optimism. He already knew a great deal about animal-rights activists’ attacks on biomedical researchers (see the excellent sixth chapter of Wesley's 2002 Culture of Death for a primer that taught us a great deal). But we were concerned that the rest of the animal rights world (pets, food, fiber, entertainment, and such) might pose too broad a subject for any one writer to cover adequately.

Happily, our worries were misplaced. A Rat Is a Pig Is a Dog Is a Boy is a winner. (We hope he doesn’t have to pay Ingrid Newkirk a royalty for that book title.) It's meticulously footnoted, full of thoughtfully told stories, and uncompromising in defense of the premise that the “boy” in its title is exceptional—that is, unlike those other three species in the ways that matter most. This book also makes a compelling case—the best we have read anywhere— for the idea that "animal rights" is a system of ideological belief as rigid (and vulnerable to unreasoning abuse) as any religion.

Since this blog is principly concerned with the Humane Society of the United States, we’ll share (with his permission) some of what Wesley writes about that organization; but know that A Rat Is a Pig is a near-encyclopedic examination of the 95 percent or so of the animal rights movement industry that Americans encounter on a regular basis. It’s a must-own volume for farmers, ranchers, dairymen, chefs, sportsmen, pet breeders, reptile hobbyists, biomedical researchers, college students, and well-meaning donors to all kinds of animal charities.

A Rat Is a Pig explores HSUS’s tactics and positions on a number of different issues, but three stand out.

First, HSUS has been quite vocal in promoting itself as a group dedicated to “nonviolence.” (See its policy statement to that effect.) Here’s Wesley’s take on how this plays out in practice:

Peter Singer has opposed violence, as has Wayne Pacelle, the head of HSUS. For example, when a medical researcher’s house was bombed in Santa Cruz, HSUS offered a token reward, a mere $2,500 from an organization with more than $200 million in assets, for the capture and conviction of the culprits—which infuriated other animal rights activists. Steven Best [the terrorism-supporting UTEP philosophy professor] blew his stack for this “treachery,” castigating Pacelle and HSUS both for publicly opposing animal rights terrorism and for the small reward it offered in the Santa Cruz bombing case. [pp. 138-139]

To this, we’ll add the observation that HSUS currently employs a senior staffer who has been outspoken in his support of animal rights terrorism in the past. And that in 2003, when an animal rights fugitive—a criminal still listed among the FBI’s “Most Wanted Terrorists”—fled to escape capture, the FBI found bomb-making materials in his car. They also found a check written to him by Ariana M. Huemer (an HSUS employee), under the driver's-side visor. (Make of that whatever you will.)

So it’s only fair that HSUS’s indignant condemnation of violence gets mixed reviews. At a minimum, you’d think HSUS’s leaders would offer a bigger reward if they were serious. They can certainly afford it.

And then there’s the hunting issue. HumaneWatch readers have already seen how, as the leader of the Fund For Animals, HSUS CEO Wayne Pacelle was one of the late 20th century’s most uncompromising opponents of hunting in every form. Wesley believes that Pacelle has softened this stance in his role with the less-radical HSUS:

[M]ost states have outlawed the harassment of hunters, to the chagrin of Wayne Pacelle, who when he worked for the Fund for Animals (now merged with HSUS) told the New York Times, “We believe we have the same right to protect wildlife as they do to shoot wildlife. These laws make it a crime to shout at an animal but it is legal to shoot an animal. This is a strange priority.” Pacelle once called for the total outlawing of hunting, telling an animal rights publication, “We are going to use the ballot box and the democratic process to stop all hunting in the United States … We will take it species by species until all hunting is stopped in California. Then we will take it state by state.” But as the head of HSUS, Pacelle has lowered his sights to argue more reasonably for the legal ban of certain types of hunts that would be found objectionable by many who do not oppose hunting in principle. For example, HSUS supports the Sportsmanship in Hunting Act, which would prohibit closed-range ranches from importing “exotic” animals not indigenous to the United States to be hunted by paying customers (a practice called “canned hunting”). HSUS also seeks to outlaw bear baiting, pheasant stocking, and hunting contests that involve killing as many animals as possible. [pp. 226-227]

For what it’s worth, we don’t think Pacelle went soft on his anti-hunting strategy as a consequence of assuming the reins at the more high-profile HSUS. It’s far more likely that he merely lengthened his timeline and changed his plan of attack. Instead of wiping out all hunting in California as a precursor to a nationwide ban, Pacelle aims to outlaw (nationally) a handful of less-easily defensible hunting practices as a precursor to clamping down on ordinary weekend sportsmen.

Last—and perhaps most telling—is the way HSUS has contorted the American legal system, exploiting every opportunity it can conjure to choke-hold its targets toward extinction. In A Rat Is a Pig, we have an excellent summary of HSUS’s courtroom battles against a tiny New York company best known for producing the delicacy foie gras:

[I]n 2006 the Humane Society of the United States filed a Federal lawsuit against Hudson Valley Foie Gras, described in the HSUS publicity release about the case as a “notorious factory farm.” Foie gras is considered by some to be an especially delicious delicacy, but animal rights/liberationists detest the manufacturing of foie gras because it is made from the livers of ducks and geese that have been fattened through forced overfeeding so that their livers swell to three times the normal size.

HSUS's lawsuit, however, technically had nothing to do with the treatment of Hudson Valley's birds, Rather, HSUS—which is not an environmental protection organization—charged the company with violating the federal Clean Water Act, contending that the farm permitted bird feces to pollute the Hudson River.

The pollution case was not the first time HSUS had filed suit against Hudson Valley Foie Gras. In another case, the animal rights group claimed that the company was delivering tainted food to the marketplace. And just months before filing the pollution suit against the farm, HSUS had lost a suit that sought to prevent New York's Empire State Development Corporation from awarding the farm a $400,000 grant intended to help it upgrade and expand its water treatment facilities. In other words, HSUS first tried to prevent Hudson Valley Foie Gras from receiving state money that would help it run a cleaner operation with regard to water pollution, and then turned right around and charged the company with polluting water. [pp. 64-65, emphasis added]

As Wesley points out, HSUS doesn’t really care about water pollution. (That is, this is not a creative way for HSUS to protect fish or waterfowl.) Rather, water pollution was merely the most convenient pretext on which HSUS could attack a duck farmer who had the temerity to resist his prescribed role in the vegan revolution.

The next logical step in this discussion, of course, is the animal rights movement’s current fascination with turning animals into legal plaintiffs. Again, Wesley is right on target:

[W]hat if instead of HSUS suing Hudson Valley for pollution violations, the company's geese could sue the company directly for abuse? What if animal liberationists could provide lawyers so that animals could bring legal cases? They could easily use their considerable budgets to pay lawyers to flood the courts with lawsuits fair and foul—and thereby tie animal industries into hopeless knots, raising their cost of doing business, and perhaps making insurance companies unwilling to provide coverage for fear of financial losses.

Animals bringing lawsuits? Don't laugh. Granting animals the right to sue—known as “legal standing”—is a major long-term goal of the animal rights movement. (Of course, it would be the liberationists who would bring the cases on behalf of the oblivious animals as their “guardians.”) Moreover, there is a dedicated cadre of lawyers and law students eagerly working toward achieving this and other legal goals of animal rights through the courts.

Observers looking for evidence of the animal rights industry moving into America’s courtrooms need only look to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, where President Barack Obama’s top “regulatory czar” (the Harvard law professor Cass Sunstein) openly advocates giving barnyard creatures the same legal standing we routinely extend to children, ships, buildings, and corporations.

Of course, this whole kind of activism—the strategic kind practiced from 36,000 feet up in the air—is precisely what HSUS’s growing legal department excels at.

If A Rat Is a Pig Is a Dog Is a Boy has a conscious theme, it is that animal rights strategists like HSUS's have stealthily woven their agenda tightly among the more ordinary threads of our society. It’s everywhere around us, devious and malevolent, at once both recklessly boastful and carefully concealed. And as the book’s subtitle announces confidently, this carries with it an unacceptable human cost.

We emphatically recommend this book for anyone who cares about the future of animal protection and fears that a once well-meaning cultural movement has gone completely off its rails. Wesley J. Smith is a studied voice of common sense whose thoughtful volume could not have come at a better time.

A RAT IS A PIG IS A DOG IS A BOY

By Wesley J. Smith

Encounter Books, 312 pp.

$17.13 at Amazon.com